Trim and Stability Analysis¶

From Part 2 we have a nonlinear state-space model of F-16 flight dynamics in the form

In Part 3 of this tutorial series on F-16 flight dynamics modeling we will take the the next step in a typical control systems development workflow; finding and analyzing the stability of trim conditions. The technical details in this part will be largely self-contained, but we will skip derivations wherever possible (and recommend referring to “Aircraft Control and Simulation” by Stevens, Lewis, and Johnson for details). The source code is available on GitHub.

The interface of our flight dynamics model is roughly:

@struct

class SubsonicF16:

@struct

class State(RigidBody.State):

pos: np.ndarray # North-East-Down position [ft]

att: Attitude # quaternion or RPY attitude

v_B: np.ndarray # Body-frame (FRD) velocity [ft/s]

w_B: np.ndarray # Body-frame angular velocity [rad/s]

eng: F16Engine.State # Engine state (may be empty)

elevator: Actuator.State # Actuator state (may be empty)

aileron: Actuator.State # Actuator state (may be empty)

rudder: Actuator.State # Actuator state (may be empty)

@struct

class Input:

throttle: float # Throttle command [0-1]

elevator: float # Elevator deflection [deg]

aileron: float # Aileron deflection [deg]

rudder: float # Rudder deflection [deg]

def net_forces(self, t, x: State, u: Input) -> tuple[np.ndarray, np.ndarray]:

"""Net forces and moments in body frame B"""

def dynamics(self, t, x: State, u: Input) -> State:

"""Compute time derivative of the state"""

As an example of how to interact with the model, take the following reference time derivative evaluation from Stevens, Lewis, and Johnson (3.5-2):

model = SubsonicF16(xcg=0.4)

u = model.Input(

throttle=0.9,

elevator=20.0,

aileron=-15.0,

rudder=-20.0,

)

# Textbook state used (Vt, alpha, beta) = (500.0, 0.5, -0.2)

# Our model uses equivalent (u, v, w) = (430.0447, -99.3347, 234.9345)

# --> (du, dv, dw) = 100.8536, -218.3080, -437.0399

pos = np.array([1000.0, 900.0, -10000.0]) # NED-frame position

rpy = np.array([-1.0, 1.0, -1.0]) # Roll, pitch, yaw

v_B = np.array([430.0447, -99.3347, 234.9345]) # Velocity in body frame

w_B = np.array([0.7, -0.8, 0.9]) # Angular velocity in body frame

att = Quaternion.from_euler(rpy)

x_eng = model.engine.State(90.0) # Set Engine power

x = model.State(pos, att, v_B, w_B, eng=x_eng)

x_t = model.dynamics(0.0, x, u)

pprint(x_t)

State(pos=array([ 342.4439, -266.7707, -248.1241]),

att=Quaternion([ 0.3624 0.465 -0.2977 0.2209]),

v_B=array([ 100.8545, -218.3043, -437.0737]),

w_B=array([12.6266, 0.965 , 0.5809]),

eng=NASAEngine.State(power=np.float64(-58.68400000000001)),

aero=F16Aero.State(),

elevator=Actuator.State(),

aileron=Actuator.State(),

rudder=Actuator.State())

Finding Trim Conditions¶

There are various ways to define “trim” conditions for an aircraft. We will define it as a (state, controls) pair such that the time derivative of body-frame velocity and angular velocity are zero:

Importantly, this means that the angular velocity may be nonzero, and hence the time derivative of inertial velocity may also be nonzero. An example of this is a coordinated turn maneuver, which is not “steady” in any traditional dynamical systems sense.

The body-frame velocity and angular velocity are the “dynamics” subset of the full vehicle state \(\mathbf{x}\), so we could write the condition above in shorthand as:

The value of \(f_\mathrm{dyn}(t, x, u)\) is our “trim residual” - we will need this to be identically zero to find a trim condition.

We will additionally specify several desired characteristics of the trim point:

True airspeed \(V_T\)

Altitude \(-z\)

Flight path (climb) angle \(\gamma\)

Roll, pitch, and yaw (turn) rates \(\dot{phi}\), \(\dot{\theta}\), \(\dot{\psi}\)

Mathematically, what we are doing is essentially a root-finding problem (though it could alternatively formulated as weighted least-squares or a more general constrained nonlinear program). Given the trim condition above as input, we want to find state and input variables such that the “quasi-steady” condition above holds.

We will use the following as our “decision variables” for this optimization problem:

Angle of attack \(\alpha\)

Sideslip angle \(\beta\)

Throttle level \(\delta_T\)

Control surface deflections \(\delta_e\), \(\delta_a\), \(\delta_r\)

This gives us six optimization parameters for six dynamic residuals - exactly what we need for a Newton-type root-finding solver.

The logical flow for the optimization problem is to take the inputs and optimization parameters, derive a full vehicle state and inputs, and then evaluate the trim residual. That is, if our input conditions are \(c\) and our optimization parameters are \(p\) we need to define functions \(x = x(c, p)\) and \(u = u(c, p)\). The the full root-finding problem is

The inputs \(u(c, p)\) are the easy part, since all of the flight control inputs are part of the optimization parameters already. That leaves the function \(x(c, p)\) which constructs a full vehicle state from the trim condition and optimization parameters.

This actually may be easier to understand in code than on paper:

@struct

class TrimCondition:

vt: float # True airspeed [ft/s]

alt: float = 0.0 # Altitude [ft]

gamma: float = 0.0 # Flight path angle [deg]

roll_rate: float = 0.0 # Roll rate [rad/s]

pitch_rate: float = 0.0 # Pitch rate [rad/s]

turn_rate: float = 0.0 # Turn rate [rad/s]

@struct

class TrimVariables:

alpha: float # Angle of attack [rad]

beta: float # Sideslip angle [rad]

throttle: float # Throttle setting [0-1]

elevator: float # Elevator deflection [deg]

aileron: float # Aileron deflection [deg]

rudder: float # Rudder deflection [deg]

@property

def inputs(self) -> SubsonicF16.Input:

return SubsonicF16.Input(

throttle=self.throttle,

elevator=self.elevator,

aileron=self.aileron,

rudder=self.rudder,

)

def trim_residual(

params: TrimVariables,

condition: TrimCondition,

model: SubsonicF16,

) -> np.ndarray:

x = trim_state(params, condition, model)

u = params.inputs

x_t = model.dynamics(0.0, x, u)

return np.hstack([x_t.v_B, x_t.w_B])

The function trim_state is \(x(c, p)\), which we have not defined yet

Deriving the Trim State¶

There are three states we don’t care about, as they play no role in the dynamics: North-East positions, and yaw angle.

The vertical position is given as part of the input conditions (negative altitude).

“Auxiliary” states like the engine and control surface actuators have their own .trim() methods built-in, so we will assume that the subsystem models can trim themselves independently of the vehicle dynamics.

This means that the main work in trim_state is deriving the body-frame velocity and angular velocity, and the pitch and roll angles.

The pitch and roll angles are the most complex - these have to be chosen carefully to ensure coordination between the velocity and angular velocity vectors. This is mainly a kinematic problem and doesn’t depend on the details of the flight vehicle itself.

The condition for the turn constraint that determines roll angle \(\phi\) is:

Once \(\phi\) is known, the pitch angle \(\theta\) can be determined with the rate-of-climb constraint:

Now we have a full roll-pitch-yaw attitude specification and Euler angle rates (given as inputs), and we can use the inverse Euler kinematic equation to solve for the corresponding body-frame angular velocity:

Finally, body-frame velocity is simply the rotation of the wind-frame velocity \(v^W = \begin{bmatrix}V_T & 0 & 0\end{bmatrix}^T\) into the body frame using the aerodynamic angles \((\alpha, \beta)\):

Here’s the full implementation:

This looks a little hairy, but it maps cleanly to the math - better yet, it doesn’t depend on the details of the model, so the same code can be reused across a wide variety of flight vehicles.

Solving the Trim Problem¶

At this point the hard work is done.

The trim function itself essentially just packs the inputs into a struct, calls root to set the optimization parameters, and returns the results for further analysis:

Now we can use this to solve for a variety of trim conditions, e.g. steady level flight at 10,000 ft:

model = SubsonicF16(xcg=0.35)

result = model.trim(vt=500.0, alt=10000.0, gamma=0.0)

pprint(result.variables)

TrimVariables(alpha=array(0.0594),

beta=array(0.),

throttle=array(0.1678),

elevator=array(-0.6531),

aileron=array(0.),

rudder=array(0.))

or a constant turn of 0.1 rad/s:

result = model.trim(vt=500.0, turn_rate=0.1, alt=10000.0, gamma=0.0)

pprint(result.variables)

TrimVariables(alpha=array(0.124),

beta=array(0.0005),

throttle=array(0.3304),

elevator=array(-1.1232),

aileron=array(0.0295),

rudder=array(-0.3269))

Stability Analysis¶

Now that we can identify trimmed conditions, the next natural question is one of stability. In principle, if we set the controls to their trimmed points and reach the right \((V_T, \alpha, \beta)\), the aircraft will keep going as intended. But what happens if we perturb away from the trimmed condition?

For a general nonlinear state-space model of the form

which is how our model is expressed, for some nominal condition \((x_0, u_0)\) and perturbations \((\delta x, \delta u)\), we can do a Taylor expansion:

where \((A, B, C, D)\) are the Jacobian matrices evaluated at the nominal condition.

The eigenvalues/vectors of \(A\) and the poles and zeros of the transfer function \(G(s) = C(sI - A)^{-1}B + D\) then give insight into what happens when we perturb away from the trim condition.

Model Decomposition¶

In our case the full state has 14 elements (13 for a RigidBody with quaternion kinematics, plus one extra for the engine state).

However, a number of these are irrelevant to stability analysis - North-East position and yaw play no role in the dynamics, and altitude is only weakly involved (through the atmosphere).

Moreover, for small perturbations it is more convenient and intuitive to represent the dynamics with Euler angles than a quaternion (unless we’re linearizing at extreme pitch angles).

Finally, we will assume the engine response is fast enough to have a negligible effect on the overall stability.

Removing these from consideration, we’re left with 8 elements in the state vector: body-frame velocity and angular velocity, plus roll and pitch angles. These can be represented in various ways; here we’ll use \((V_T, \alpha, \beta)\) for velocity and Euler angles for attitude. This truncated state can be split into two weakly-coupled blocks (almost completely decoupled, in steady level flight):

Longitudinal |

Lateral-Directional |

|

|---|---|---|

States |

Airspeed \(V_T\) |

Sideslip \(\beta\) |

Angle of Attack \(\alpha\) |

Roll Angle \(\phi\) |

|

Pitch Angle \(\theta\) |

Roll Rate \(p\) |

|

Pitch Rate \(q\) |

Yaw Rate \(r\) |

|

Inputs |

Throttle \(\delta_T\) |

Aileron \(\delta_a\) |

Elevator \(\delta_e\) |

Rudder \(\delta_r\) |

To derive decoupled linearized models, the general procedure is to define a function that evaluates the derivatives of the reduced state. For example, to evaluate the longitudinal derivatives, this function must:

Expand the longitudinal state into a full vehicle state, filling in lateral-directional values from the trim condition

Evaluate the time derivative of the full vehicle state

Extract the longitudinal components of the full time derivative

Then this function must be linearized about the longitudinal trim condition.

Typically, this process involves manually managing entries of flat vectors (e.g. x_lon[0] = x_full[6] for airspeed) and using careful finite differencing for the Jacobian.

In our case we can lean on struct representations of the state and flatten/unflatten as needed, so we can define structured types for the reduced states.

The general interface used for our tutorial is:

@struct

class LongitudinalState:

vt: float

alpha: float

theta: float

q: float

@classmethod

def from_full_state(cls, x: SubsonicF16.State) -> LongitudinalState:

"""Extract longitudinal components of the full state"""

def as_full_state(self) -> SubsonicF16.State:

"""Expand the reduced state into a full state"""

@struct

class LongitudinalInput:

throttle: float

elevator: float

@struct

class LateralState:

beta: float

phi: float

p: float

r: float

# ... similar from_, as_ methods

@struct

class LateralInput:

aileron: float

rudder: float

@struct

class StabilityState:

lon: LongitudinalState

lat: LateralState

@classmethod

def from_full_state(cls, x: SubsonicF16.State) -> StabilityState:

"""Extract the truncated stability state variables"""

def as_full_state(self) -> SubsonicF16.State:

"""Expand the truncated state to a full nonlinear vehicle state"""

@classmethod

def from_full_derivative(

cls, x: SubsonicF16.State, x_dot: SubsonicF16.State

) -> StabilityState:

"""Compute the time derivatives of truncated stability state variables"""

@struct

class StabilityInput:

lon: LongitudinalInput

lat: LateralInput

Once again, this is much more verbose than the simpler manual array management approach, and may not be well suited for all applications. That said, it does tend to be more scalable and maintainable to have the dependencies and data flow be explicit without things like hardcoded indexing.

Longitudinal Stability¶

With this interface, we can define abstracted reduced dynamics and output functions:

Then the linearization is as simple as calling the jac for automatic differentiation:

A, B = arc.jac(lon_dynamics, argnums=(1, 2))(0.0, x0_flat, u0_flat)

C, D = arc.jac(lon_output, argnums=(1, 2))(0.0, x0_flat, u0_flat)

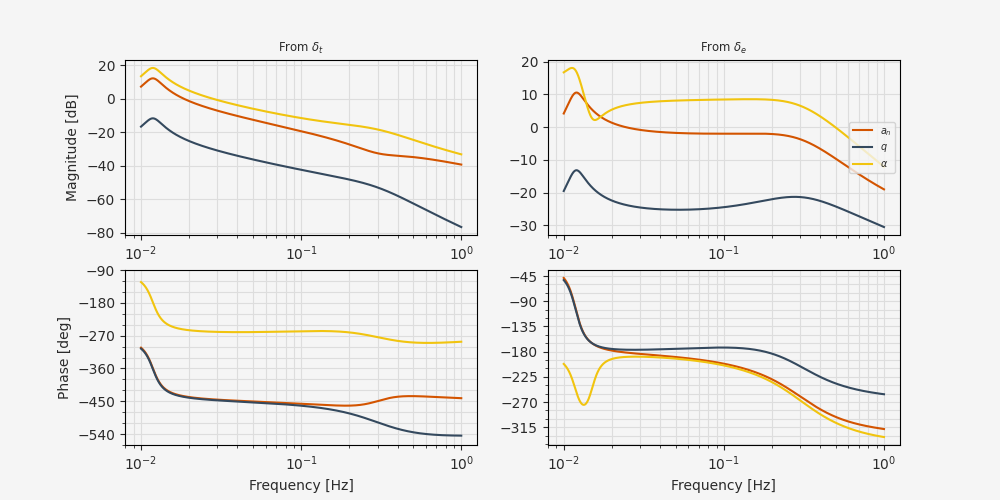

input_labels = [r"$\delta_t$", r"$\delta_e$"]

output_labels = [r"$a_n$", r"$q$", r"$\alpha$"]

sys = control.ss(

A, B, C, D, inputs=input_labels, outputs=output_labels, name="longitudinal"

)

sys

Now we can assess the well-known modes of the system:

evals = np.linalg.eigvals(A)

phugoid_idx = np.argmax(evals.real)

short_idx = np.argmax(evals.imag)

print(

f"Phugoid mode:\t\t{evals[phugoid_idx].real:.4f} ± {evals[phugoid_idx].imag:.4f}j"

)

print(f"Short period mode:\t{evals[short_idx].real:.4f} ± {evals[short_idx].imag:.4f}j")

Phugoid mode: -0.0087 ± 0.0740j

Short period mode: -1.2038 ± 1.4920j

and its open-loop behavior:

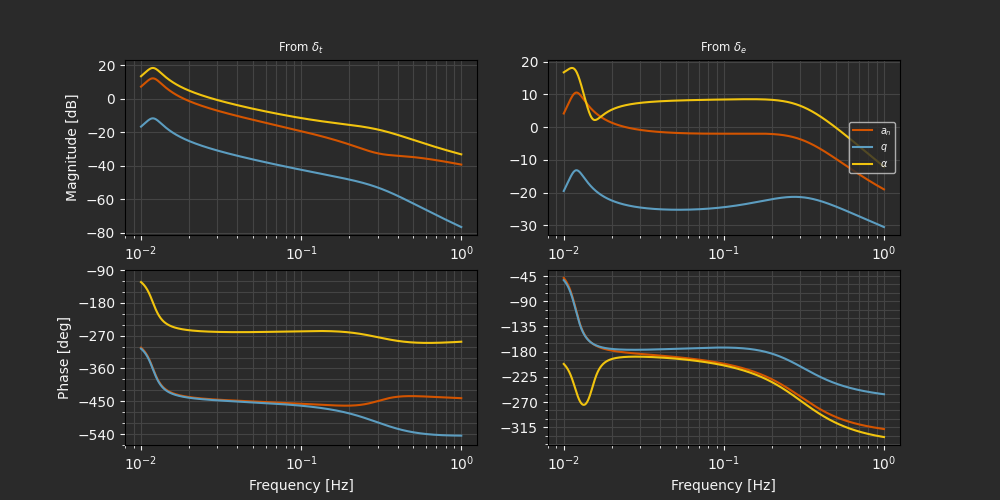

Lateral-directional Stability¶

The lateral-directional analysis proceeds almost identically:

These linearized systems are the typical starting point for control systems design, since they provide relatively small, intuitive models for cascaded control and various CAS/SAS/autopilot loops.