Configuration Management¶

In Part 1 of this series we covered the recommended standard design patterns for creating hierarchical models of complex dynamical systems. These are “rules” you are free to break; they are not enforced anywhere and come down to your own preferences and style.

Continuing on this theme, in Part 2 we will discuss a recommended approach to configuration management for hierarchical models. You are free to implement this, ignore it, or rebuild your own configuration management system as you see fit.

Warning

This part of the series uses some fairly advanced Python features - feel free to scan and skip it if it doesn’t seem relevant for what you’re doing right now. Configuration management is only really necessary when building up relatively complex models and it’s not hard to retrofit a framework that was written without it, so don’t let the complexity keep you from getting started.

The Problem¶

As your hierarchical models become more complex, it becomes increasingly tedious and error-prone to manually create all of the various subsystems and properly pass them to their parent subsystems and so on. Given that some component models may have multiple variants, your code will also need logic to correctly initialize the variants, which might include setting up lookup tables, pre-calculating some parameters, or validating that the configuration is valid.

All of this becomes increasingly difficult to maintain as models grow in depth and complexity, particularly when implementing the “multi-fidelity” concept.

Decoupling the Configuration¶

The recommended solution to this in Archimedes is to put this configuration logic in a separate class that inherits from StructConfig.

This is basically a Pydantic BaseModel tailored for use with @struct-decorated classes.

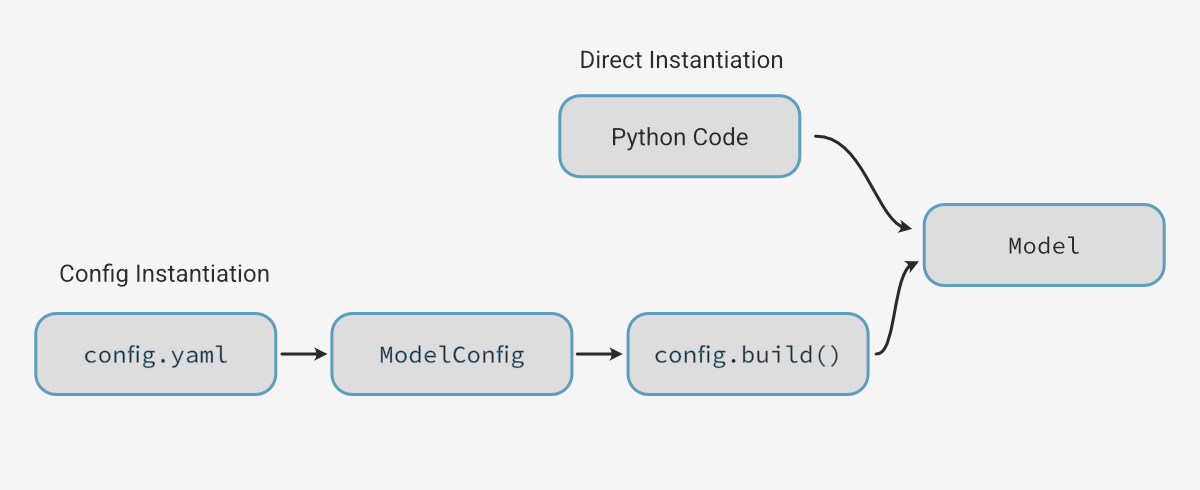

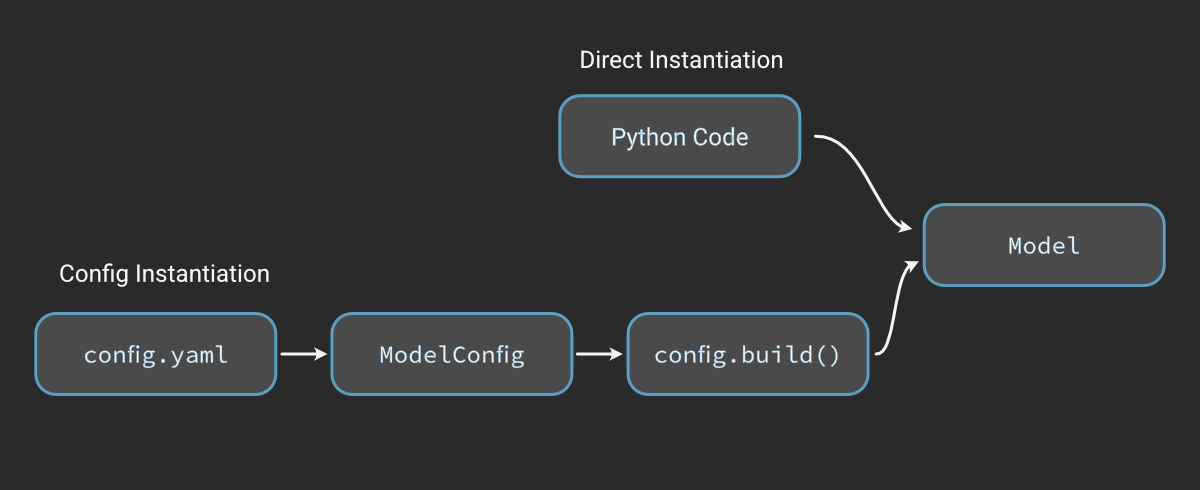

This gives you two paths to creating your struct - directly in code, or by loading a config file (YAML is easy, JSON or something else if you prefer).

Here’s what it looks like, reusing the Oscillator example from Part 1:

# NOTE: Unchanged from Part 1 code

@struct

class LinearOscillator:

"""A basic mass-spring-damper component."""

m: float # Mass

k: float # Spring constant

b: float # Damping constant

@struct

class State:

"""State variables for the mass-spring-damper system."""

x: float

v: float

def dynamics(self, t, state: State, f_ext: float = 0.0) -> State:

"""Compute the time derivatives of the state variables."""

f_net = f_ext - self.k * state.x - self.b * state.v

return self.State(x=state.v, v=f_net / self.m)

# We just add a second "config" class

class LinearOscillatorConfig(StructConfig, type="linear"):

m: float # Mass

k: float # Spring constant

b: float # Damping constant

def build(self) -> LinearOscillator:

# Can do some validation/pre-processing here

if self.m < 0:

raise ValueError("Mass must be non-negative")

if self.k < 0:

raise ValueError("Spring constant must be non-negative")

if self.b < 0:

raise ValueError("Damping constant must be non-negative")

return LinearOscillator(m=self.m, k=self.k, b=self.b)

Previously we initialized this manually:

system = Oscillator(m=1.0, k=1.0, b=0.1)

We can still do that, of course, but now we have the additional option of initializing via config:

config = {

"m": 1.0,

"k": 10.0,

"b": 0.5,

}

osc = LinearOscillatorConfig.model_validate(config).build()

We can now also create a model from a configuration file.

For instance, if we have a config.yaml written as simply:

m: 1.0

k: 10.0

b: 0.5

we can load with:

with open("config.yaml", "r") as f:

config = yaml.safe_load(f)

osc = LinearOscillatorConfig.model_validate(config).build()

This is all fairly verbose and doesn’t get us anything except the additional validation step, but again, it pays dividends when working with more complicated models.

This separate config class also results in a bit of boilerplate in terms of repeated parameter names (but please let us know if you know of a better way to do it!), but the advantage is that the decoupling means you can have configurations that use totally different parameters from the final component.

Note

For those familiar with Pydantic: since StructConfig is a BaseModel, you can use all of the typical decorators and other validation mechanisms.

Configuration Unions¶

You may have noticed that when we created the LinearOscillatorConfig we passed an additional type="linear" argument when defining the class.

This defines a string-literal type field for the class with whatever name you choose, which can be used to distinguish the model from other variants of the same component model.

As discussed in Part 1, it is strongly recommended to formalize the component interface with an abstract base class or Protocol definition when there are multiple variants.

Note

A Protocol is a way to define an interface for typing that allows you to specify a set of methods and attributes that an object must possess to be considered compatible with that protocol.

Think of it as a way of documenting and formalizing an interface that’s less strict than an abstract base class (though you may want to use those as well).

Here’s what the protocol looks like:

class Oscillator(Protocol):

@struct

class State:

x: float

v: float

def dynamics(

self, t, state: Oscillator.State, f_ext: float = 0.0

) -> Oscillator.State: ...

Note that this just dictates what the state will contain (at a minimum), and what the signature of the dynamics method will be.

This is the interface.

Beyond that, the Oscillator protocol doesn’t require us to have any particular parameters or assume any details about how dynamics is implemented.

You might think of the Oscillator as a “generic” oscillator component that we could fill with any class that fits this profile.

As a side note, if you do have components that have shared functionality or want to more strongly enforce that they have certain behaviors, an abstract base class with explicit inheritance is probably the way to go.

Also note that the LinearOscillator we created already implements this interface, so we already have a valid Oscillator type!

Now we can implement other oscillator variations, for instance adding a cubic nonlinearity:

# Implement a weakly nonlinear variation of the oscillator

@struct

class DuffingOscillator:

m: float # Mass

a: float # Linear stiffness coefficient

b: float # Nonlinear stiffness coefficient

c: float # Damping coefficient

@struct

class State:

x: float

v: float

def dynamics(

self, t: float, state: Oscillator.State, f_ext: float = 0.0

) -> Oscillator.State:

"""Compute the time derivatives of the state variables."""

# Compute derivatives

f_net = f_ext - self.a * state.x - self.b * state.x**3 - self.c * state.v

# Return state derivatives in the same structure

return self.State(x=state.v, v=f_net / self.m)

class DuffingOscillatorConfig(StructConfig, type="duffing"):

m: float # Mass

a: float # Linear stiffness coefficient

b: float # Nonlinear stiffness coefficient

c: float # Damping coefficient

def build(self) -> DuffingOscillator:

# Can do some validation/pre-processing here

if self.m < 0:

raise ValueError("Mass must be non-negative")

if self.a < 0:

raise ValueError("Linear stiffness coefficient must be non-negative")

if self.c < 0:

raise ValueError("Damping coefficient must be non-negative")

return DuffingOscillator(m=self.m, a=self.a, b=self.b, c=self.c)

Next we define a UnionConfig that registers both of these variants using the “types” we gave them.

OscillatorConfig = UnionConfig[

LinearOscillatorConfig,

DuffingOscillatorConfig,

]

It will be easier to see what this UnionConfig is doing shortly, when we actually use it in a composite model.

Using Generic Components¶

Now we have defined a Protocol (or abstract base class, if you prefer) for a generic Oscillator.

We’ve also defined a UnionConfig for this generic oscillator that knows how to dispatch to the different concrete implementations based on the “type” name.

For example, we can now reuse our CoupledOscillators model from Part 1 with no change.

To do this, we define a top-level StructConfig that uses our UnionConfig to declare that we expect to get either a LinearOscillatorConfig or a DuffingOscillatorConfig:

class CoupledOscillatorsConfig(StructConfig):

osc1: OscillatorConfig

osc2: OscillatorConfig

coupling: float

def build(self) -> CoupledOscillators:

if self.coupling < 0:

raise ValueError("Coupling constant must be non-negative")

return CoupledOscillators(

osc1=self.osc1.build(),

osc2=self.osc2.build(),

coupling=self.coupling,

)

Creating Configurable Models¶

At this point, it may be a bit unclear why we went to all of this trouble.

How do we use these “type” identifiers?

What’s the point of the generic Oscillator?

The magic is that now that we’ve build up all of this machinery, we can simply modify a YAML file (or JSON, if you prefer) to swap between component variants.

For example, the following config file will couple one linear and one nonlinear oscillator:

osc1:

type: linear

m: 1.0

k: 4.0

b: 0.1

osc2:

type: duffing

m: 1.0

a: 1.0

b: 5.0

c: 0.02

coupling: 5.0

We can load this just as before:

with open("osc_config.yaml", "r") as f:

config = yaml.safe_load(f)

system = CoupledOscillatorsConfig.model_validate(config).build()

pprint(system)

CoupledOscillators(osc1=LinearOscillator(m=1.0, k=4.0, b=0.1),

osc2=DuffingOscillator(m=1.0, a=1.0, b=5.0, c=0.02),

coupling=5.0)

Changing the component type or parameters is as simple as editing the config file, making it easy to run multiple side-by-side analyses or version-control configurations.

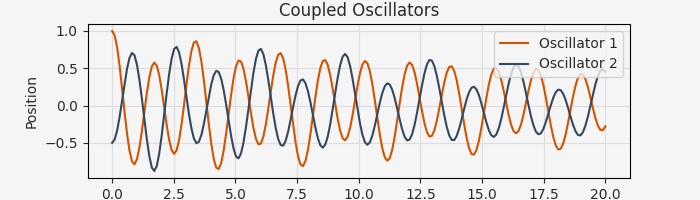

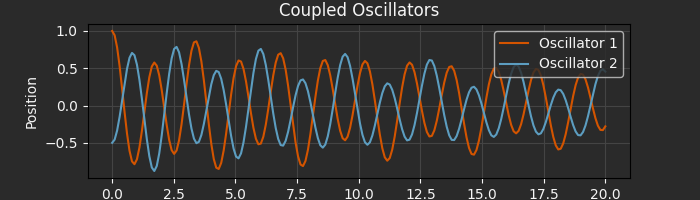

Finally, we can simulate with confidence using the exact same code as Part 1, since we’ve clearly defined all of our interfaces!

Summary¶

Setting up a configuration management system admittedly takes a bit of extra work compared to just implementing a hierarchical model as described in Part 1. It’s not always necessary - for the oscillator model in particular it’s clearly overkill.

But there are some definitive advantages to investing the time in this when you’re working with more complex models. Proper configuration management lets you:

Implement validation checks on configuration and parameters

Decouple initialization/configuration logic from “runtime” implementation

Easily track and version-control parameters independent of the application code

Switch between variations of components to explore different parameterizations, physics models, or implement a full multi-fidelity modeling system

Clearly define generic interfaces and their relationship to concrete component implementations

You don’t always need it - but when you do, now you know how to do it right.