Spatial Mechanics¶

Inside the new spatial module

Jared Callaham • 16 Oct 2025 (Updated 5 Nov 2025)

Release v0.3.1 marks the graduation of the spatial module out of experimental status and into production.

This module includes core functionality for 3D vehicle dynamics modeling in a range of domains.

In this post we’ll introduce the most important members of this module: the Attitude protocol and RigidBody class.

These let you represent 3D rotations and 6dof rigid body dynamics in a way that’s extensible, customizable, and compatible with the rest of Archimedes, including C code generation, autodiff, and tree operations.

We’ll cover:

Why you might want to use the

spatialmoduleAttitude representations and the

Attitudeprotocol6dof dynamics and the

RigidBodyclassBuilding your own vehicle models

What’s next for

spatial

Note

This post serves as an announcement of these new features, but will also be updated to provide a basic reference for the relevant conventions and equations. Most recent update: 5 Nov 2025 (v0.4.0)

What spatial Does¶

The spatial module is designed for cross-domain spatial mechanics.

This means that there’s no specific physics modeling like aerodynamics or gravity, but there are reusable components that come in handy across a wide range of application areas; satellites, airplanes, rockets, drones, watercraft, and cars can all use the same basic spatial dynamics primitives.

The module is built on two main capabilities: 3D rotation representations, and 6dof rigid body dynamics. We’ll cover these next.

What’s not in spatial¶

This module does not (yet) handle any multibody dynamics - RNA, CRB, contact mechanics, etc. - although this is on the longer-term roadmap.

Much sooner on the roadmap, spatial will eventually add functionality for spatial transforms combining translation and rotation, plus kinematic tree data structures to handle complex and moving reference frame situations (common in robotics and orbital mechanics, for instance).

In short, the current functionality is useful for 3D orientations and when simulating isolated rigid bodies in 3D (especially vehicle dynamics), but not for full-fledged multibody systems including joints and collisions.

TL; DR¶

Here’s a “quickstart” version of the capabilities in spatial.

First, working with attitudes and rotations:

import numpy as np

import archimedes as arc

from archimedes.spatial import Attitude, EulerAngles, Quaternion, RigidBody

# Define a roll-pitch-yaw sequence representing the attitude of body B with respect

# to inertial earth frame E

rpy = EulerAngles([0.1, 0.2, 0.3], seq="xyz")

# Convert to a rotation matrix that transforms vectors from frame E to frame B

R_BE = rpy.as_matrix()

v_E = np.array([1.0, 0.0, 0.0])

v_B = R_BE @ v_E

# Inverse transformation

v_E = R_BE.T @ v_B

# Convert between representations

q = rpy.as_quat()

# Same operations in either representation

R_BE = q.as_matrix()

v_B = R_BE @ v_E

6-dof rigid body dynamics:

# Rigid body dynamics

t = 0

x = RigidBody.State(

pos=np.zeros(3), # Inertial position

att=rpy,

v_B=np.array([10.0, 0.0, 0.0]), # Body-frame velocity

w_B=np.zeros(3), # Body-frame angular velocity

)

u = RigidBody.Input(

F_B=np.array([0.0, 0.0, 10.0]), # Body-frame forces

M_B=np.array([0.0, 1.0, 0.0]), # Body-frame moments

m=10.0, # Mass

J_B=np.eye(3), # Inertia matrix

)

x_t = RigidBody.dynamics(t, x, u) # Calculate time derivatives

# Can use either attitude representation

x = x.replace(att=q)

x_t = RigidBody.dynamics(t, x, u) # Automatically uses quaternion kinematics

This works because the Attitude protocol lets you write type-safe “polymorphic” functions that work with any attitude representation (basically, fancy old school duck-typing):

def body_frame_kinematics(

att: Attitude, v_B: np.ndarray, w_B: np.ndarray

) -> tuple[np.ndarray, Attitude]:

R_EB = att.as_matrix().T

pos_deriv = R_EB @ v_B # Inertial-frame velocity

att_deriv = att.kinematics(w_B) # Attitude kinematics

return pos_deriv, att_deriv

v_B = np.array([10.0, 0.0, 0.0])

w_B = np.array([0.0, 1.0, 0.0])

dp_E, drpy = body_frame_kinematics(rpy, v_B, w_B) # Euler kinematics

dp_E, dq = body_frame_kinematics(q, v_B, w_B) # Quaternion kinematics

That’s basically all you need to know to start working with spatial, but read on for a deeper dive.

3D Rotations¶

Direction cosine matrices, Euler angles, and quaternions are all representations of 3D rotations - how one frame or body is oriented relative to another in space.

Archimedes represents these rotations using the Attitude protocol and classes that implement this abstract interface, most importantly EulerAngles and Quaternion.

The Attitude interface is largely patterned on SciPy’s Rotation class, but deviates from SciPy in several ways that make it more convenient for flexible dynamics modeling.

Note

Active and Passive Rotations: Archimedes adopts a passive rotation convention for coordinate frame transformations. This differs for example from SciPy’s active rotation convention, which rotates vectors in a single coordinate frame. The rotation matrices used in either cases are transposes of each other.

Active and passive rotations¶

There are at least three ways to think about a “3D rotation”:

The orientation of a body B relative to frame A (e.g. the roll-pitch-yaw sequence you would apply to reach the current attitude)

A coordinate transformation from a vector from frame A to frame B

An SO(3) rotation transformation applied to a vector

The first two are mathematically equivalent and are inverse to the third. The first two represent a change of coordinates of a fixed “abstract” vector; the numbers in the array change, but they represent the same physical quantity (e.g. a force or velocity). This is by convention called a “passive” rotation since the vector itself doesn’t change.

The third case represents a transformation of the vector itself in a single coordinate system. In this case the vector moves, and so the rotation is called “active”.

For example, if we have an aircraft that is at a roll angle \(\phi\), we might want to know what the force of gravity is in body-fixed coordinates. In the North-East-Down “earth” frame E, gravity is

To get the body-frame gravity vector we apply a rotation \(\mathbf{R}_{BE}\) defined by the attitude of the vehicle:

In code, this looks like:

F_grav_E = np.array([0, 0, m*g0])

R_BE = EulerAngles(phi, "x").as_matrix()

F_grav_B = R_BE @ F_grav_E

This is a passive rotation because the force vector is the same; the coordinates are what rotate. This is a more common situation in physics and engineering, where vectors are physical quantities that we express in various convenient coordinate systems. The “passive” interpretation is the default in Archimedes

On the other hand, suppose we have a mesh with \(N\) vertices defined by a (3, N) array and we want to visualize this at a roll angle of \(\phi\).

One way to look at this situation is that the vertices are defined in a “body” coordinate system (the original mesh coordinates), and the “earth” coordinate system is what the graphing library will use.

In this case the transformation we need is \(\mathbf{R}_EB = \mathbf{R}_BE^T\), which will go from the body frame B to the world frame E.

Alternatively, we could view this as an “active” rotation of the vertex points to the new orientation; in either case \(\mathbf{R}_EB\) is the correct transformation.

In code, this is the inverse transformation:

R_EB = EulerAngles(phi, "x").as_matrix().T

p_E = R_EB @ p_B # (3, N)

This kind of “active” transformation is more common in computer graphics and is taken as the default interpretation of a “rotation” in SciPy, for example. The key thing to remember is that Archimedes treats the vector as a frame-independent physical quantity and rotates the coordinates, not the vector itself. However, as seen in the previous code snippet, the “active” behavior can be recovered by simply inverting the transformation.

The Attitude protocol¶

The interface expected by rotation representations is defined by an Attitude protocol that looks like the following:

class Attitude(Protocol):

def as_matrix(self) -> np.ndarray:

"""Convert the attitude to a direction cosine matrix (DCM)"""

def rotate(self, vectors: np.ndarray, inverse: bool = False) -> np.ndarray:

"""Rotate vectors with the transformation represented by the attitude"""

def inv(self) -> Attitude:

"""Compute the inverse of the rotation corresponding to the attitude."""

def kinematics(self, w_B: np.ndarray) -> Attitude:

"""Compute the time derivative of the attitude given angular velocity."""

The two current implementations of this protocol are EulerAngles and Quaternion, both of which additionally support indexing, iteration, and conversions back and forth.

This design departs from SciPy’s Rotation class, which always uses an quaternion representation internally but has flexible constructor methods (from_euler) and conversion to arrays (as_euler).

The difficulty with this for dynamics modeling is that quaternions are not always the best choice.

Quaternions are a good default, since they provide a minimal, singularity-free representation of 3D rotations, but Euler angles are more intuitive for applications like stability analysis of flight dynamics and when working with vehicles like cars that are unlikely to reach gimbal lock.

Additionally, some specialized applications like trajectory optimization might use representations like modified Rodrigues parameters that do not require the unit-norm constraint of quaternions.

What the Attitude protocol buys us is polymorphism.

You can write code that accepts an Attitude and expect to use any of the methods above safely, regardless of what the representation is.

For example, the position and attitude kinematics calculation in RigidBody looks roughly like:

def kinematics(

att: Attitude, v_B: np.ndarray, w_B: np.ndarray

) -> tuple[np.ndarray, Attitude]:

R_EB = att.as_matrix().T

pos_deriv = R_EB @ v_B # Inertial-frame velocity

att_deriv = att.kinematics(w_B) # Attitude kinematics

return pos_deriv, att_deriv

This function will work for any class that properly implements the Attitude spec, meaning that you can freely swap between Euler angles, quaternions, custom attitude parameterizations, etc. without any reconfiguration or special handling.

Quaternions¶

The Quaternion implementation closely follows SciPy’s Rotation and is unit tested directly against the SciPy behavior.

However, by re-implementing it in Archimedes we can ensure that it is compatible with the Attitude spec as well as all of the symbolic-numeric capabilities like autodiff and codegen.

# Rotate a vector from the inertial earth frame E to the body frame B if the body's

# attitude is given by (roll, pitch, yaw) Euler angles rpy

def to_body(rpy, v_E):

att = Quaternion.from_euler(rpy, seq="xyz")

R_EB = att.as_matrix()

return R_EB @ v_E

rpy = np.array([0.1, 0.2, 0.3])

v_E = np.array([10.0, 0.0, 0.0])

print(arc.jac(to_body)(rpy, v_E)) # dv_E/drpy

[[ 0. -1.89796061 -2.89629478]

[ 2.18350663 0.93473365 -9.56425086]

[ 2.75095847 9.31615797 0.36957014]]

As with the SciPy implementation, a Quaternion can be instantiated from a rotation matrix (DCM), another quaternion, or any combination of Euler angles, giving you a lot of flexibility in how you think about representing your attitude while still providing a robust representation of 3D rotations.

Note

Another difference from the SciPy version is that by default Archimedes uses a scalar-first component ordering, more common in engineering applications compared to, for instance, computer graphics.

Archimedes also diverges from SciPy by implementing the Attitude interface; namely, by providing a kinematics method that calculates quaternion kinematics, assuming the rotation represents the orientation of a moving body with respect to some reference frame.

Given the angular velocity of the body in its own frame, \(\omega_B\), this function calculates the time derivative of the rotation using quaternion kinematics:

The actual implementation of quaternion kinematics differs slightly from the ideal form by adding a “Baumgarte stabilization” to numerically preserve the unit-norm requirement. With a stabilization factor of \(\lambda\), the full kinematics model is:

A factor of \(\lambda = 1\) is a good default (and is the default in RigidBody as well).

att = Quaternion.from_euler(rpy, "xyz")

w_B = np.array([0.0, 0.1, 0.0]) # 0.1 rad/sec pitch-up

att.kinematics(w_B)

Quaternion([-0.00530103 -0.00717861 0.04916737 0.00171354])

Caution

The kinematics method returns the time derivative of the Quaternion as a new Quaternion instance.

This is convenient for working with ODE solvers and other algorithms that expect the output to have the same structure as the input state.

However, keep in mind that the time derivative \(\dot{\mathbf{q}}\) is not itself a valid rotation.

Hence, you CANNOT use att.kinematics(w_B).as_euler("xyz") to get the Euler angle rates.

If you need Euler rates, use Euler kinematics directly: att.as_euler("xyz").kinematics(w_B).

This attitude kinematics calculation comes in particularly handy for the second major functionality released with spatial: 6dof rigid body dynamics modeling.

Euler angles¶

The EulerAngles class has a similar interface to Quaternion, differing mainly in construction and interpretation.

The class allows you to specify a sequence seq of rotation axes as a string of 1-3 letters 'x', 'y', and 'z'.

These are interpreted as sequential rotations about each axis to go from a “parent” or “world” frame to the body frame specified by the attitude.

For example, the typical roll-pitch-yaw sequence for vehicle dynamics is specified by seq="xyz" and is interpreted as a right-handed rotation about the world-frame \(x\)-axis, followed by a rotation about the new \(y\)-axis and finally a rotation about the subsequent \(z\)-axis.

Note

EulerAngles supports “intrinsic” rotations (use upper-case letters, as in the SciPy convention), but here we’ll mostly discuss the “extrinsic” convention with lower-case axis sequences.

Mathematically, EulerAngles(rpy, seq="xyz").as_matrix() produces the following matrix, representing a coordinate transform from “earth frame” E to “body frame” B with rpy a 3-element array of roll \(\phi\), pitch \(\theta\), and yaw \(\psi\):

This sequence can be used to flexibly represent a variety of coordinate transformations, for instance:

# Simple rotation about a single axis from A -> B

R_BA = EulerAngles(theta, "z")

# Standard roll-pitch-yaw sequence

R_BE = EulerAngles(rpy, seq="xyz")

# Rotation from wind frame W with (α, β) to body frame B

R_BW = EulerAngles([-beta, alpha], seq="zy")

# Rotation from ECI frame to perifocal in orbital mechanics

R_PE = EulerAngles([ω, i, Ω], "zxz")

The EulerAngles representation can easily be converted to/from other representations like Quaternion, or betweeen sequences:

rpy = EulerAngles([0.1, 0.2, 0.3], seq="xyz")

q = rpy.as_quat() # Quaternion([0.98334744 0.0342708 0.10602051 0.14357218])

ypr = rpy.as_euler("zyx") # EulerAngles([0.2857717 0.22012403 0.03787988], seq='zyx')

For the Euler-to-Euler conversion, note that the as_euler(seq) requires a sequence of exactly three non-repeating axes in order to guarantee a complete representation in the output.

That is, rpy.as_euler("x") will raise an error since this is mathematically undefined.

Finally, EulerAngles implements Euler kinematics for the roll-pitch-yaw sequence "xyz" only.

This converts body-frame angular velocity \(\boldsymbol{\omega}^B\) to Euler angle rates:

rpy = EulerAngles([0.1, 0.2, 0.3], seq="xyz")

w_B = np.array([0.0, 0.1, 0.0]) # Angular velocity

drpy_dt = rpy.kinematics(w_B)

Caution

As with Quaternion.kinematics, the EulerAngles.kinematicsmethod returns the time derivative of the EulerAngles as a new EulerAngles instance.

This is convenient for working with ODE solvers and other algorithms that expect the output to have the same structure as the input state.

However, keep in mind that the time derivative of the Euler angles are not themselves a valid rotation representation.

In almost all cases, the only thing you should do with the Euler rates is integrate them to get the time series of angles.

Low-level rotation API¶

If the Attitude system isn’t your thing and you prefer an interface closer to MATLAB’s Aerospace Toolbox - or if you want to implement your own system for attitude and rotation representation - there are also lower-level functions that operate directly on arrays.

The low-level functions are:

Each of these do exactly what they sound like - see the docstrings for details.

These functions are called by wrapper classes like Quaternion and EulerAngles for conversions and kinematics, so you get the same behavior and performance either way - it’s just a matter of which interface you prefer.

6dof Dynamics¶

A “6dof” rigid body has three translational and three rotational “degrees of freedom” from the point of view of Lagrangian mechanics. From a state-space modeling perspective, this system has either 12 or 13 dynamical states (depending on whether you use Euler or quaternion kinematics). The rigid body dynamics model implements the equations of motion of such a body given specified forces, torques, and mass/inertia characteristics.

The Archimedes RigidBody implementation follows the conventions of the classic GNC textbook “Aircraft Control and Simulation” by Stevens, Lewis, and Johnson.

Hence, the terminology and implementation is heavily based on flight dynamics applications, though this can be adapted straightforwardly to other domains.

For an in-depth description of the conventions, notation, and derivation of the equations of motion, refer to the textbook.

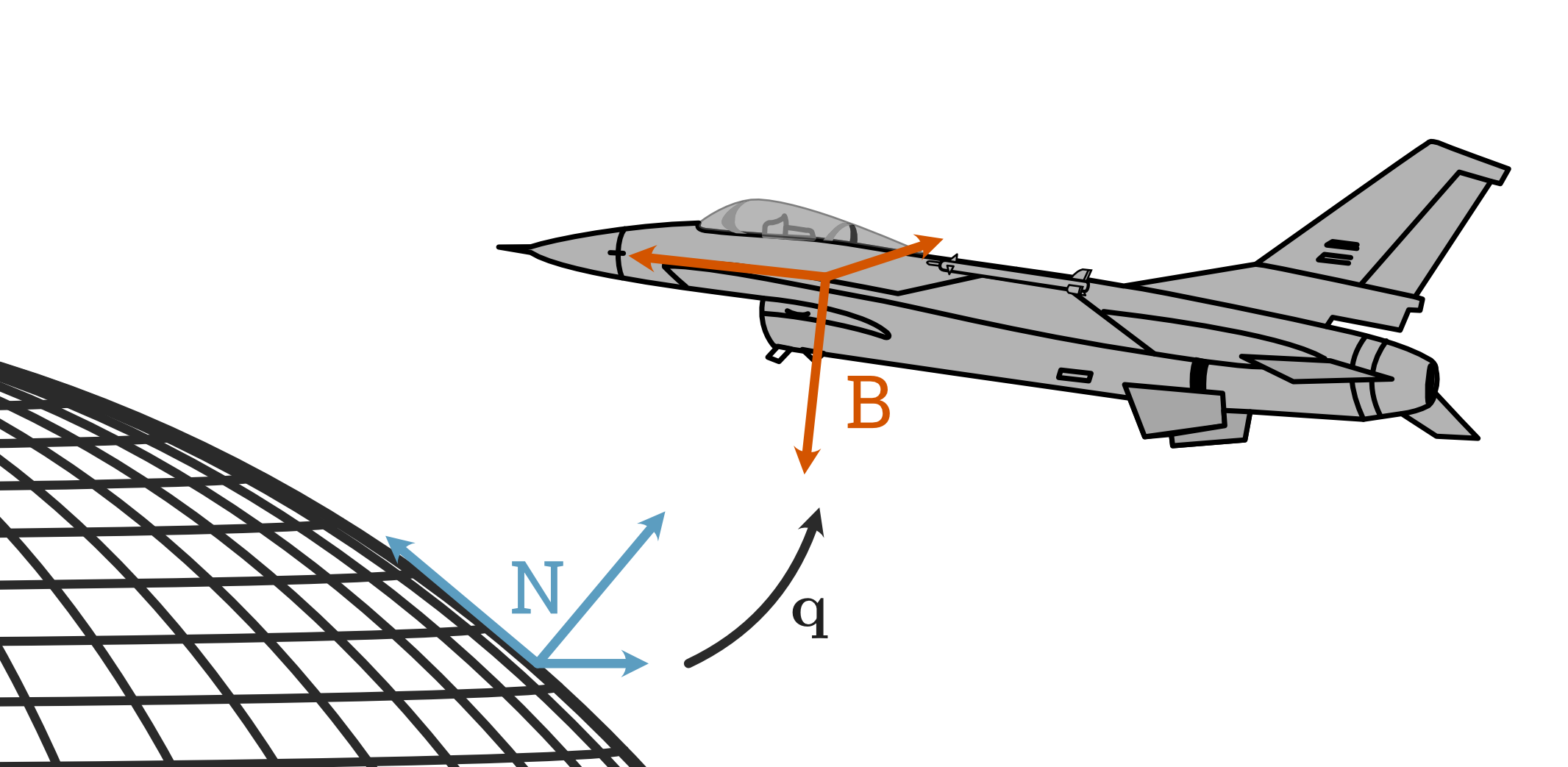

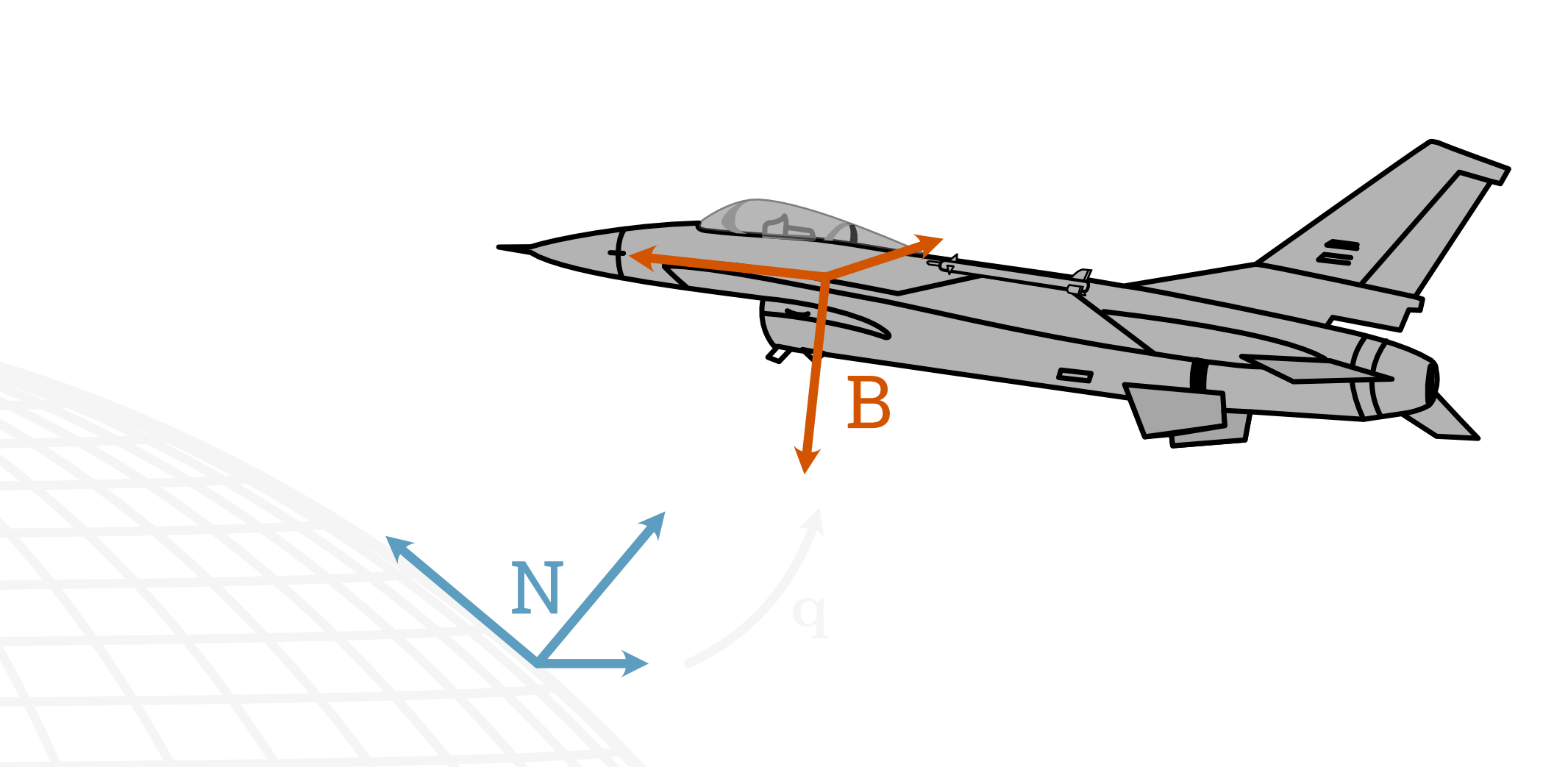

Our rigid body model assumes two reference frames: a body-fixed frame “B” with the origin at the center of mass, and a Newtonian inertial frame “N” (for instance the world or ground frame in flight dynamics).

Vectors are suffixed following monogram notation to indicate coordinate systems unless it is clear. In this convention, the dynamical states for a rigid body are four vectors:

pos: the position of the body in the inertial frame (\(\mathbf{p}^N\))att: the attitude of the body with respect to the inertial framev_B: the translational velocity of the body in its own coordinate system B (\(\mathbf{v}^B\))w_B: the body-relative angular velocity vector (\(\boldsymbol{\omega}^B\))

The governing equations for these four state components depend on the applied forces and moments in the body frame (\(\mathbf{F}^B\) and \(\mathbf{M}^B\), respectively), as well as on the mass \(m\) and inertia matrix \(J_B\) of the vehicle. If the mass and/or inertia matrix are changing significantly in time, their time derivatives can also be provided (we’ll ignore this here, since this is uncommon).

Then the equations of motion are:

Note

The choice to use body-frame rather than inertial velocity may be surprising, given that the evolution equation then requires the non-inertial term \(\boldsymbol{\omega}^B \times \mathbf{v}^B\).

This is done for two reasons.

First, in many applications forces are more naturally expressed in body-frame coordinates, so working with body-frame velocities avoids an extra rotation (though integrating velocity to position requires the rotation anyway, so this is basically a wash).

More importantly, choosing to represent both the translational and angular velocity in the body frame is consistent with “Plücker coordinates”, which will become the common representation of motion and forces as the spatial module grows to encompass multibody dynamics (think recursive Newton-Euler, composite rigid body, etc.).

For more, see “Looking Ahead” below - and don’t worry, if you’ve never heard of Plücker coordinates you won’t need to learn them to use this module.

The RigidBody class exists to calculate these equations for a generic body - you just have to provide forces, moments, mass, and inertia characteristics.

The idea is that you can use this as a building block and construct your own vehicle models (or models of whatever it is you’re building) by implementing the domain-specific physics models and letting Archimedes handle the generic parts.

Implementation¶

The RigidBody class structure looks roughly like the following:

@struct

class RigidBody:

rpy_attitude: bool = False # If True, use roll-pitch-yaw for attitude

baumgarte: float = 1.0 # Baumgarte stabilization factor for quaternion kinematics

@struct

class State:

pos: np.ndarray # Position of the center of mass in the Newtonian frame N

att: Rotation | np.ndarray # Attitude (orientation) of the vehicle

v_B: np.ndarray # Velocity of the center of mass in body frame B

w_B: np.ndarray # Angular velocity in body frame (ω_B)

@struct

class Input:

F_B: np.ndarray # Net forces in body frame B

M_B: np.ndarray # Net moments in body frame B

m: float # mass [kg]

J_B: np.ndarray # inertia matrix [kg·m²]

dm_dt: float = 0.0 # mass rate of change [kg/s]

# inertia rate of change [kg·m²/s]

dJ_dt: np.ndarray = field(default_factory=lambda: np.zeros((3, 3))) # type: ignore

def dynamics(self, t: float, x: State, u: Input) -> State:

...

See the source code for the actual implementation.

The inner classes State and Input help to organize the data and states, and the dynamics method does the work of actually calculating the equations of motion as given above.

Note

On time-varying mass/inertia: it is relatively common to have vehicles that change mass and inertia properties over time (e.g. a rocket burning fuel).

RigidBody takes these as inputs so that you can manage their characteristics however you want.

Technically, when the mass and inertia are time-varying this adds terms like \(\dot{m} v_B\) to the dynamics equations.

Under most circumstances these contributions are negligible even if \(\dot{m} \neq 0\).

The compromise model in this case is the “quasi-steady” approximation: provide time-varying mass \(m(t)\) as inputs to the dynamics method, but leave \(\dot{m} = 0\).

If the mass/inertia rate-of-change terms are significant, they can be included as “pseudo-forces” - see below for details.

While RigidBody uses quaternion kinematics by default for stability and robustness - critical for vehicles like satellites, quadrotors, and fighter jets - there is also the option to use roll-pitch-yaw Euler kinematics for bodies like cars and ships that (nominally) won’t reach 90-degrees pitch-up and hit the gimbal lock singularity.

In these cases you can set rpy_attitude = True and use a roll-pitch-yaw sequence instead of the Rotation for the attitude representation.

Here’s the RigidBody class in action:

x = RigidBody.State(

pos=np.array([0.0, 0.0, 10.0]),

att=Quaternion.identity(),

v_B=np.zeros(3),

w_B=np.zeros(3),

)

u = RigidBody.Input(

F_B=np.array([0.0, 0.0, 9.8]),

M_B=np.array([0.0, 0.1, 0.0]),

m=10.0,

J_B=np.eye(3),

)

RigidBody.dynamics(0.0, x, u)

RigidBody.State(pos=array([0., 0., 0.]), att=Quaternion([0. 0. 0. 0.]), v_B=array([0. , 0. , 0.98]), w_B=array([0. , 0.1, 0. ]))

In this simple case, since the body and world axes are aligned (Rotation.identity()) and we start out with zero angular velocity, most of the complexity from non-inertial frames in the equations of motion disappears. and we just get \(m \dot{\mathbf{v}}^B = \mathbf{F}^B\) and \(\mathbf{J}_B \dot{\boldsymbol{\omega}}^B = \mathbf{M}^B\).

Customizing with pseudo-forces and moments¶

The equations of motion implemented here are technically correct only for the case of a rigid body with constant mass, inertia, and center of gravity moving in an inertial reference frame and without “internal” angular velocity (gyroscopic effects). However, the model can be extended to account for these effects if needed by passing pseudo-forces and moments.

In all the following cases, the effects can be treated as constant, quasi-steady (time-varying but with negligible rates), or fully dynamic (time-varying with non-negligible rates). In both cases, the current value and time derivatve should be tracked and computed outside of the rigid body model, and the appropriate values passed in the input struct.

Variable mass: Quasi-steady mass may be handled by passing the current mass in the input struct. The mass rate of change \(\dot{m}\) enters the equations of motion via the time derivative of linear momentum:

\[\frac{d}{dt}(m \mathbf{v}^B) = \mathbf{F}^B \implies m \dot{\mathbf{v}}^B + \dot{m} \mathbf{v}^B = \mathbf{F}^B\]Hence, mass flow rates can be accounted for by including the pseudo-force \(-\dot{m} \mathbf{v}^B\) in the net forces passed as input.

Variable inertia: In the same way, quasi-steady inertia may be handled by passing the current inertia matrix in the input struct. The inertia rate of change \(\dot{\mathbf{J}}^B\) enters the equations of motion via the time derivative of angular momentum:

\[\frac{d}{dt}(\mathbf{J}^B \boldsymbol{\omega}^B) = \mathbf{M}^B \implies \mathbf{J}^B \dot{\boldsymbol{\omega}}^B + \dot{\mathbf{J}}^B \boldsymbol{\omega}^B = \mathbf{M}^B\]Non-negligible inertia rates can be accounted for by including the pseudo-moment \(-\dot{\mathbf{J}}^B \boldsymbol{\omega}^B\) in the net moment passed as input.

Variable center of mass: The equations of motion are derived about the center of mass (CM). However, typically the body-fixed reference frame B is defined at some convenient reference point that may not coincide with the instantaneous center of mass. Properties like aerodynamics and propulsion behaviors are also often defined with respect to the reference CM.

If the reference CM is at the origin of the body frame B and the actual CM is at a point \(\mathbf{r}_{CM}^B\) in body frame B moving with velocity \(\dot{\mathbf{r}}_{CM}^B\) with respect to the reference point, then the relationship between the state velocity \(\mathbf{v}^B\) (that is, the inertial velocity of the CM expressed in body frame B) and the velocity of the reference point \(\mathbf{v}_{ref}^B\) is

\[\mathbf{v}^B = \mathbf{v}_{ref}^B + \dot{\mathbf{r}}_{CM}^B + \boldsymbol{\omega}^B \times \mathbf{r}_{CM}^B\]Often this correction is negligible, but if needed then the state velocity should be converted to the reference point velocity before computing aerodynamics or other quantities referenced to the body frame origin. In the common case that the CM is moving due to fuel consumption or payload release, the relative velocity \(\dot{\mathbf{r}}_{CM}^B\) is usually negligible.

A more important effect is the moment transfer from the offset of the forces acting at the reference point to the actual CM. If the net force acting on the vehicle at the reference point is \(\mathbf{F}_{ref}^B\), then the moment about the CM is given by

\[ \mathbf{M}^B = \mathbf{M}_{ref}^B - \mathbf{r}_{CM}^B \times \mathbf{F}_{ref}^B\]The same transformation applies to forces computed about an arbitrary reference point, but the moment arm will then be the vector from that reference point to the instantaneous CM.

Gyroscopic effects: The full Euler equation for rotational dynamics in a non-inertial body-fixed frame is

\[ \mathbf{M}^B = \frac{d\mathbf{h}^B}{dt} + \boldsymbol{\omega}^B \times \mathbf{h}^B,\]where \(\mathbf{h}^B\) is the net angular momentum of the vehicle in the body frame B. If the vehicle does not have any “internal” angular momentum, then \(\mathbf{h}^B = \mathbf{J}^B \boldsymbol{\omega}^B\) and the equations reduce to those implemented here.

However, if there are significant additional contributions to angular momentum, these affect the dynamics via gyroscopic pseudo-moments. If a system has internal angular momentum \(\mathbf{h}_{int}^B = \sum_{i} \mathbf{J}_{int,i}^B \boldsymbol{\omega}_{int,i}^B\), these contributions must be included:

\[ \mathbf{M}^B = \frac{d}{dt}(\mathbf{J}^B \boldsymbol{\omega}^B) + \frac{d\mathbf{h}_{int}^B}{dt} + \boldsymbol{\omega}^B \times \mathbf{J}^B \boldsymbol{\omega}^B + \boldsymbol{\omega}^B \times \mathbf{h}_{int}^B\]The additional terms involving \(\mathbf{h}_{int}^B\) can be treated as pseudo-moments and included in the net moment passed as input. The usual logical flow would be to compute both the internal angular momentum and its time derivative outside of the rigid body model (e.g. as a subsystem calculation), and then pass the net effective moment

\[ \mathbf{M}_\mathrm{eff}^B = \mathbf{M}^B - \frac{d}{dt}(\mathbf{h}_{int}^B) - \boldsymbol{\omega}^B \times \mathbf{h}_{int}^B\]as the input to the rigid body dynamics.

For example, a calculation of the gyroscopic effects of a spinning rotor with inertia \(\mathbf{J}_\mathrm{rot}^B\), angular velocity \(\boldsymbol{\omega}_\mathrm{rot}^B\), and negligible angular acceleration might look like:

h_int_B = J_rot_B @ w_rot_B # Rotor angular momentum # Compute effective moment including gyroscopic effects M_eff_B = M_B - np.cross(w_B, h_int_B)

Time-varying subsystem inertias \(\mathbf{J}_{int,i}^B\) can also be handled in this way and show up as a pseudo-torque in the effective net moment.

Non-inertial frames¶

These equations of motion are valid only when referenced to a Newtonian inertial frame N. This is of course an idealization in all cases, but it is always possible to find some frame that is nearly enough inertial for modeling purposes.

A common situation in aerospace applications is to model a body moving relative to a rotating planetary frame E (e.g. the Earth-centered, Earth-fixed frame ECEF) that is assumed to be in non-accelerating but rotating with some angular velocity \(\boldsymbol{\Omega}_{E}\) with respect to the inertial frame N. In this case an alternative formulation uses a state vector composed of:

\(\mathbf{p}^E\) = position of the center of mass in the frame E

\(\mathbf{q}\) = attitude (orientation) of the vehicle with respect to E

\(\mathbf{v}^E\) = velocity of the center of mass in rotating frame E

\(\boldsymbol{\omega}^B\) = angular velocity in body frame (ω_B) with respect to the inertial frame N

The equations of motion in this formulation are:

Unfortunately, this cannot be straightforwardly reconciled with the implementation here, even with the addition of the Coriolis and centrifugal pseudo-forces. This is because of the definition of the attitude and angular velocity with respect to different reference frames (E and N, respectively). Using the angular velocity relative to frame N allows the use of the Euler dynamics equation without complex pseudo-moments, but means that the angular velocity must be modified by \(-\boldsymbol{\Omega}_{E}^B\) in the attitude kinematics.

The equations above could be implemented in an ECEF frame with a simple custom rigid body class:

@struct

class EarthReferencedBody:

rot_earth: float = 7.292e-5

@struct

class State:

pos: np.ndarray # ECEF position

att: Attitude # Body attitude relative to ECEF

v_E: np.ndarray # ECEF velocity

w_B: np.ndarray

@struct

class Input:

F_E: np.ndarray # Forces in Earth frame

M_B: np.ndarray # Moments in body frame

m: float # Mass

J_B: np.ndarray # Inertia matrix in body frame

def dynamics(self, t: float, x: State, u: Input) -> State:

Ω_E = np.hstack([0.0, 0.0, self.rot_earth])

R_BE = x.att.as_matrix()

v_E, p_E = x.v_E, x.pos # ECEF position, velocity

# Position and attitude kinematics

pos_deriv = v_E

att_deriv = x.att.kinematics(x.w_B - x.w_B - R_BE @ Ω_E)

# Force equation with Coriolis and centrifugal effects

dv_E = (u.F_E / u.m) - np.cross(Ω_E, 2 * v_E - np.cross(Ω_E, p_E))

# Moment equation (same as body-referenced formulation)

dw_B = np.linalg.solve(

u.J_B, u.M_B - np.cross(x.w_B, u.J_B @ x.w_B)

)

# Output time derivatives of substates

return RigidBody.State(

pos=pos_deriv, att=att_deriv, v_E=dv_E, w_B=dw_B

)

While this formulation does cover a substantial number of orbtial mechanics applications, it is not one-size-fits all. Are centrifugal effects accounted for in the gravity model? Are precession and nutation important? Is the angular velocity time-varying? The present design prioritizes customization over comprehensiveness.

In short, handling of non-inertial frames in Archimedes still needs some design work and is not robustly supported. The recommendation is to implement custom rigid body dynamics based on the above equations. If you would like to see support for non-inertial frames be a higher priority, please feel free to raise the issue in the Discussions page on GitHub.

Custom Vehicle Models¶

The power of RigidBody comes from being able to use this as a component inside more complex vehicle models.

Two basic patterns you might use for this are inheritance and composition.

Inheritance¶

With this pattern, the vehicle model simply inherits from RigidBody directly.

This is convenient when there are no additional state variables in the model, for instance with a flight dynamics model that uses lookup tables for aerodynamics and propulsion models:

@struct

class Aircraft(RigidBody):

m: float

J_B: np.ndarray

@struct

class Input:

throttle: float

rudder: float

aileron: float

elevator: float

def calc_aero(

self, x: RigidBody.State, u: Aircraft.Input

) -> tuple[np.ndarray, np.ndarray]:

"""Calculate aerodynamic forces and moments"""

def calc_eng(

self, x: RigidBody.State, u: Aircraft.Input

) -> np.ndarray:

"""Calculate engine thrust"""

def dynamics(

self, t: float, x: RigidBody.State, u: Aircraft.Input

) -> RigidBody.State:

# Aerodynamics and propulsion models

F_aero_B, M_aero_B = self.calc_aero(x, u)

F_eng_B = self.calc_eng(x, u)

# Use the state attitude to calculate gravity in body axes

F_grav_N = self.m * np.hstack([0, 0, 9.81])

R_BN = x.att.as_matrix()

F_grav_B = R_BN @ F_grav_N

# Net forces/moments

F_B = F_aero_B + F_eng_B + F_grav_B

M_B = M_aero_B

# Use RigidBody.dynamics to evaluate the equations of motion

u_rb = RigidBody.Input(F_B=F_B, M_B=M_B, m=self.m, J_B=self.J_B)

return super().dynamics(t, x, u_rb)

Composition¶

For more complex models it is usually more convenient to instead treat the RigidBody as one component of several.

This can be a more natural way to organize hierarchical state variables:

@struct

class Aircraft:

gravity: GravityModel

atmosphere: AtmosphereModel

aero: AeroModel

engine: EngineModel

m: float

J_B: np.ndarray

@struct

class State(RigidBody.State):

aero: AeroModel.State

engine: Engine.State

@struct

class Input:

throttle: float

rudder: float

aileron: float

elevator: float

def dynamics(

self, t: float, x: Aircraft.State, u: Aircraft.Input

) -> Aircraft.State:

# Aerodynamics and propulsion models

F_aero_B, M_aero_B = self.aero.output(x, u)

F_eng_B = self.engine.output(x, u)

# Time derivatives of aerodynamic and engine states

x_aero_dot = self.aero.dynamics(x, u)

x_eng_dot = self.engine.dynamics(x, u)

# Use the state attitude to calculate gravity in body axes

F_grav_N = self.gravity(x.rigid_body.pos)

R_BN = x.rigid_body.att.as_matrix()

F_grav_B = R_BN @ F_grav_N

# Net forces/moments

F_B = F_aero_B + F_prop_B + F_grav_B

M_B = M_aero_B

# Evaluate the equations of motion

u_rb = RigidBody.Input(F_B=F_B, M_B=M_B, m=self.m, J_B=self.J_B)

x_rb_dot = RigidBody.dynamics(x, u_rb)

return self.State(

pos=x_rb_dot.pos,

att=x_rb_dot.att,

v_B=x_rb_dot.v_B,

w_B=x_rb_dot.w_B,

aero=x_aero_dot,

engine=x_eng_dot,

)

Now the aerodynamic state can handle lag effects or other unsteady aerodynamic behavior, and the engine can have its own internal dynamics as well.

This can be a much more flexible and powerful approach - since the Aircraft implementation doesn’t handle the details of any of these subsystems, it’s easy to create and test a range of different component models.

For instance, the engine model here could be anything from a simple linear thrust approximation to a detailed physics-based propulsion system model including turbomachinery and combustion calculations.

Note

For a deeper dive on hierarchical modeling in Archimedes, check out the tutorial series, which goes into detail on the @struct decorator, recommended design patterns, and configuration management for complicated hierarchical models.

We’ll be releasing more in-depth examples of different vehicle dynamics models soon, so be sure to sign up for the mailing list to stay in the loop.

Looking Ahead¶

We’ve covered a lot of ground already, so this isn’t the place for a lengthy design doc or roadmap, but it’s worth mentioning where this is headed.

Again, the 6dof rigid body state has four components:

pos: the position of the body in the inertial frame (\(\mathbf{p}^N\))att: the attitude of the body with respect to the inertial frame (\(\mathbf{q}\))v_B: the translational velocity of the body in its own coordinate system B (\(\mathbf{v}^B\))w_B: the body-relative angular velocity vector (\(\boldsymbol{\omega}^B\))

In state-space dynamics modeling, it’s natural to think of this as a 13-element state vector. However, from a spatial mechanics point of view, this is really a representation of two things:

A coordinate system B defined relative to N by a translation \(\mathbf{p}^N\) and orientation \(\mathbf{q}\).

The translational and rotational motion of the body in coordinate system B

Let’s take a brief technical digression, which you can feel free to skim if uninterested.

In spatial geometry lingo, the numerical representation of the motion are the “Plücker coordinates”, meaning that \(\mathbf{v}^B\) and \(\boldsymbol{\omega}^B\) together form an element of the 6D space of spatial motions \(M^6\). Likewise, the input combination of body-frame forces and moments are also expressed in Plücker coordinates, so \(\mathbf{F}^B\) and \(\mathbf{M}^B\) together form an element of the 6D space of spatial forces \(F^6\), dual to \(M^6\).

Getting back to practical terms, what this means is that we can layer on top of the Attitude and RigidBody concepts two new abstractions: a Transformation (translation + attitude) and a 6D SpatialVector (element of \(M^6\) or \(F^6\)).

Transformations¶

A Transformation is basically a combination of a position and an orientation, sometimes called a homogeneous transformation.

This could be applied to points (both translation and rotation) or pure vectors (rotation only).

A sketch of the implementation would look something like the following:

@struct

class Transformation

t: np.ndarray # Translation (3,)

r: Attitude

def apply(self, pos: np.ndarray) -> np.ndarray:

return self.t + self.apply_vec(pos)

def apply_vec(self, vec: np.ndarray) -> np.ndarray:

R = self.r.as_matrix()

return R @ vec

def inv(self) -> Transformation:

...

The Transformation concept will also let us create kinematic trees - a way to express relationships between various reference frames and coordinate systems.

The API design for both the Transformation and KinematicTree are still fairly hazy, but the goal is to eliminate much of the bookkeeping associated with the exploding numbers of coordinate systems common in orbital mechanics and robotics applications, for instance.

Ideally, you would simply define the relationships between the frames (including how they evolve with time) and be able to simply call:

X_BE = ktree.get_transform("earth", "body")

r_B = X_BE.apply(r_E) # ECEF -> NED tangent plane -> body frame

Multibody dynamics¶

While Transformation and kinematic trees would be convenient for keeping track of complicated arrangements of coordinate systems, the 6D spatial vectors open up more exciting possibilities.

This is because this abstraction maps directly to Roy Featherstone-style spatial vector algebra, including generalized spatial velocity, force, inertia, and associated constraints between multibody motion.

If we can set up a way to intuitively work with these vectors, we can get clean, performant implementations of powerful algorithms like Recursive Newton-Euler, Compositite Rigid Body, and the Articulated Body Algorithm. These are the cornerstones of constrained multibody dynamics - that is, robotics.

Once we have transformations, kinematic trees, spatial vectors, and rigid body algorithms, we can then layer on 3D contact and collision models to get a true robotics simulator along the lines of MuJoCo or Drake.

Now, there are existing options for all kinds of robotics work out there already (MuJoCo and Drake being my personal favorites), so you may well ask: why build another robotics simulator? The basic premise is that robotics will continue to converge with other engineering disciplines, so even outside of “traditional” robotics we’ll see more articulation, more underactuation, and more autonomy. Putting capabilities for robotics-type work under the same roof as flight dynamics, orbital mechanics, battery modeling, lumped-parameter multiphysics models, etc. with deployment capabilities could make it easier to build almost anything you can think of.

Multibody dynamics and contact won’t be coming for a while, and the plans could certainly change between now and then, but it’s worth mentioning now because (as you can see from the choice to use body-frame velocity) these plans will inform the design and priorities of the spatial mechanics functionality well before we can simulate anything that looks like a robot.

Parting Thoughts¶

The new spatial module is the first core physics modeling functionality in Archimedes, but this is just the beginning.

For spatial itself, the next priorities are spatial transformations (transformation + rotation), kinematic trees for handling multiple reference frames, and interpolations (slerp) for trajectory generation and optimization.

Beyond spatial, we’ll be adding some common functionality for different classes of vehicle models, such as reference gravitational and atmospheric models like WGS84 and USSA1976.

Tools for detailed propulsion systems modeling are more niche and thus farther out on the roadmap, but there are proof of concept demos already, so feel free to reach out if you’re interested in that.

Finally, to see this module in action check out the Subsonic F-16 series, where we implement the NASA F-16 benchmark from scratch, relying heavily on spatial for attitude representations and 6dof dynamics.

More detailed application examples will be released soon to provide full reference implementations of different classes of vehicle dynamics models (particularly aerospace-related, but also reach out if there’s something else you’d like to see).

Speaking of getting in touch, if you’re interested in this topic or Archimedes more generally, be sure to:

⭐ Star the Repository: This shows support and interest and helps others discover the project

📢 Spread the Word: Think anyone you know might be interested?

🗞️ Stay in the Loop: Subscribe to the newsletter for updates and announcements

The GitHub Discussions page is also a great place to give feedback, ask questions, or share any projects you want to use Archimedes for. Bug reports, feature requests, and complaints about documentation quality are invaluable for open-source projects like Archimedes; these are also welcome on the Issues tab.